When it comes to learning to read, the two main approaches that dominate the school system in English-speaking countries are balanced literacy and structured literacy, also referred to as “The Science of Reading” (SOR) approach by many people these days.

In recent times, an increasing number of education professionals have advocated for a shift from the “balanced literacy” curriculum in favor of a structured, phonics-centric approach “science of reading” curriculum.

How should educators and parents navigate this evolving landscape to provide the best possible education for their students?

*Affiliate Disclosure: Some links lead to Amazon marketplace. As an Amazon associate, I earn from qualifying purchases, at no additional cost to you). This helps keep the information on the blog free and available to everyone.

Balanced vs. Structured Literacy: The Origins

The debate Balanced Literacy vs. Structured Literacy (in line with the Science of Reading principles) has shaped reading instruction for years.

For decades the balanced literacy approach totally dominated reading instruction. During the 90’s and the early 2000’s teachers were heavily trained in this type of reading instruction.

However, the pendulum gradually swinging towards a new perspective.

Many schools are shifting towards “The Science of Reading” approach. Still, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t many advocates of the balanced literacy approach.

What exactly is going on?

Why are so many people shifting? Who is right?

What are the differences between balanced literacy and structured literacy?

What system delivers better results? What does scientific research have to say about this?

These are the answers we’ll respond to in this article.

Balanced Literacy: Finding a Middle Ground

“Balanced Literacy” earned its name by attempting to strike a balance between two methods for teaching reading: the whole-word/whole-language approach and phonics.

These methods are radically different. In a nutshell:

– The “whole-word” method involves memorizing lists of words without explicit phonics instruction, relying on context and cues. It’s also called the look/say approach.

– Phonics, on the other hand, teaches children the letter-sound relationships to decode words systematically.

These conflicting methods have led to what’s been termed “Reading wars” throughout history.

Until the late 1920’s phonics was the predominant method used for teaching reading. However, a new anti-phonics movement had started to emerge a few years back, and it was gaining popularity really fast.

So much so that by the 1930’s phonics – meaning explicit teaching of the code – had been abandoned in most classrooms.

This is when the whole-word approach replaced phonics.

However, poor results in reading instruction prompted a resurgence of interest in phonics. It was clear that something was wrong with the adopted model for teaching reading.

Many people, such as Rudolf Flesch, in the iconic book “Why Johnny Can’t Read”(1955) and in its sequel “Why Johnny Still Can’t Read” (1981), or Jeanne Chall, in the book “Learning to Read: The Great Debate” (1967), started to advocate moving back to the phonics model.

So, in the 70’s something changed again.The pendulum did not fully move towards phonics though. Instead, the look/say approach evolved, and a new movement started.

Welcome to the whole-language approach!

The whole-language approach, again, rejected explicit phonics instruction.

In their opinion, phonics was boring and unnecessary, and it killed the love for reading.

Their approach to teaching reading was this: rely on children’s -according to them- innate capacity to learn to read, develop a love for reading, surround children by books.

The whole-language approach incorporated real children’s stories instead of artificial readers. Unfamiliar words were not sounded out, but identified through guessing based on context.

Despite its differences from the look/say approach, the whole-language approach also involved memorizing sight words and guessing, with very limited phonics instruction.

The whole-language approached gained rapid popularity in the US, despite a lack of supporting research for its effectiveness.

In 1983, reading researchers David Share and Anthony Jorm introduced the Self-Teaching Hypothesis, emphasizing the importance of independent word decoding in reading.

Skilled readers’ extensive vocabularies made rote memorization or context-based guessing simply not possible. The necessity of decoding unknown words using letter-sound relationships and blending phonemes was exposed.

This put Share and Jorm in direct contrast to the whole-language methodology.

Besides, reading scores were still static and poor.

This led to major inquiries into how teaching reading was carried out. For instance, the 1998 report “Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children,” which is normally referred to as “The Snow Report,” or the meta-analysis from the National Reading Panel, in the year 2000.

Both reports highlighted the importance of phonics and phonemic awareness in reading instruction.

This led to the emergence of “Balanced Literacy,” which sought to integrate strategies from both phonics and whole-language approaches.

Balanced literacy emerged both as a truce between phonics and the whole-language approach, and as a response to the limitations of the whole language approach.

But, what does this even mean? How can you reconcile two methods to teaching reading that are so radically different?

It is, in fact, extremely tricky… But in the next section, we’ll look at the common strategies the balanced literacy applies in practice.

What strategies does the balanced literacy approach use?

Balanced literacy involves:

- Phonics instruction to some degree. This can be in the form of alphabet warm-ups, songs, lessons and activities around letters and sounds, etc. It is also quite common to have “the letter of the week,” especially in pre-school settings.However, in balanced literacy, there’s not a clear guidance on how to teach phonics, or how much phonics needs to be taught. Is it explicit instruction? Or implicit instruction (that is when the learning is incidental)? How structured and systematic is it? How much phonics is actually taught: are we just talking about a little bit of phonics here and there?

- Word memorization, such us word shapes. Sight word lists tend to be a pivotal strategy used in balanced literacy.

- Encouraging children to rely on clues and cues to “read” unfamiliar words, rather than decoding. For instance, the context, look at the picture or text predictability.

- Using leveled readers, as opposed to phonetically-decodable books with beginner readers.

- Using authentic text.

- Teacher read-alouds.

- Shared reading.

- Independent reading.

- Grouping children based on their reading level.

- Sharing and reflection

Unfortunately, the balanced literacy approach leaves too much room for open interpretation. This apparent flexibility might sound attractive, but it leaves important things in the air.

Besides, some of the strategies it heavily relies on can be detrimental. For instance, encouraging children to guess rather than to sound out words, or being okay with children skipping words or saying a different word altogether, provided the meaning of the word is the same.

In a way, it also moves away the responsibility from the teacher on to the student. This marries well with the belief that children have an innate ability to learn to read (this was a whole-language belief, which has been debunked by science) in the same way they learn to speak.

Science has proved the belief that we are wired for learning to read (as we are wired for learning to speak) is wrong.

Understanding how wrong this belief has enormous and serious implications on the way we teach reading.

The Science of Reading: A Research-Based Approach

You have probably have heard the term “The Science of Reading” thrown at you multiple times lately.

So much so that you could be wondering: Is it a fad? Is it an ideology or a political agenda? Is it a curriculum? Or this just a fancy term for phonics?

None of that!

If you go to the Reading League’s website, they define “The Science of Reading” as ‘a vast, interdisciplinary body of scientifically-based research about reading and issues related to reading and writing.’

In other words, researchers come from multiple fields, including psychology, education, linguistics, neuroscience

and more disciplines, are trying to find answers to best practices in reading instruction based on SCIENCE rather than based on ideology or philosophies, as it was common place in the past.

With this information, practitioners (educators, tutors, parents) can SELECT and implement practices about reading that will be the most effective for the most students.

What conclusions should a practitioner take into consideration, according to the Science of Reading (SOR)?

We’ll briefly summarize the most important ones in this video, but if you want to learn more about this topic, we strongly suggest that you also consult some of resources that we will list out for you at the end of this artcile.

To understand how a student develops into a skillful reader, the Science of Reading looks toward two frameworks, that are fully aligned with science.

1. Simple View of Reading

Empirically validated by numerous studies, this model explains that reading comprehension results from the product, not the sum, of two components: word recognition and language comprehension.

If either of these components is weak, reading comprehension suffers.

By the way, the term ‘sight word recognition’ has nothing to do with remembering whole words! It is a term widely used these day to express something like “automatic decoding.” When readers apply their knowledge of the code immediately and without any apparent attention.

This may look simple or even obvious.

However, let’s illustrate how it works with an example, so you can fully understand the implications this framework has; and why the keyword here is PRODUCT, not SUM.

What would happen if we assigned a score (1/0) to these components involved in skillfull reading and multiply?

Let’s see:

WORD RECOGNITION (0) x LANGUAGE COMPREHENSION (0) = 0

WORD RECOGNITION (1) x LANGUAGE COMPREHENSION (0) = 0

WORD RECOGNITION (0) x LANGUAGE COMPRENSION (1) = 0

Only when both components are positive, you get a positive result.

WORD RECOGNITION (1) x LANGUAGE COMPREHENSION (1) = 1

No amount of skill in one component can compensate for the other!

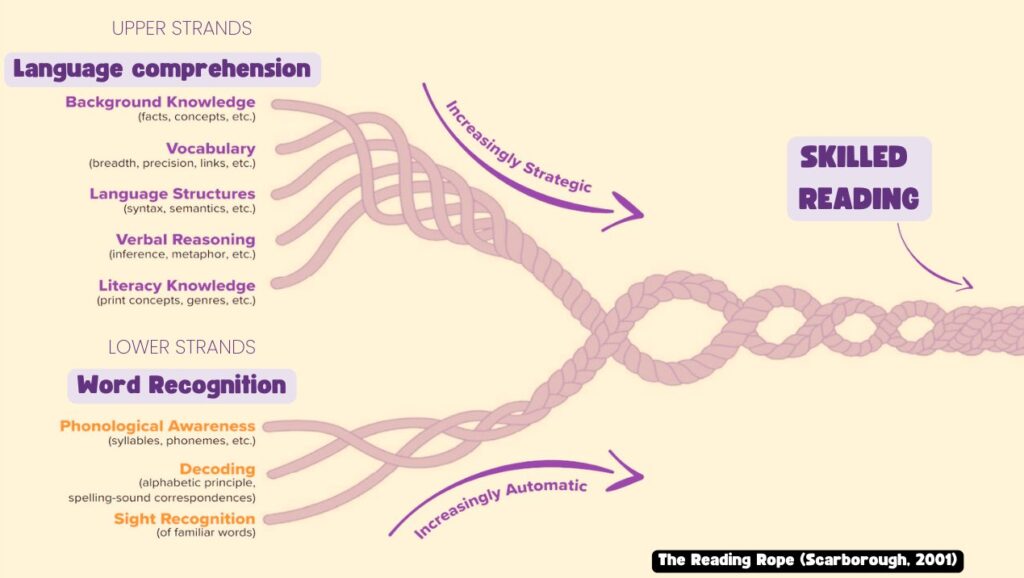

2. Scarborough’s Reading Rope

This rope, created by Scarborough in 2001, is a visual metaphor for the development of skills over time (represented by the strands of the rope) that lead to skilled reading.

This rope allows us visually understand the complexity involved in the process of learning to read.

All of these different “strands” of the rope are all interconnected, but are also independent from each other.

Scarborough’s Reading Rope is made up of lower and upper strands.

The lower strands include:

- Phonological awareness (syllables, phonemes, etc.).

- Decoding (includes the alphabetic principle and letter-sound correspondences).

- Sight recognition (of familiar words).

The upper strands include:

- Background knowledge.

- Vocabulary.

- Language structures.

- Verbal reasoning.

- Literacy knowledge.

When all these component parts intertwine, the result is skilled, accurate, fluent reading with strong reading comprehension.

Why is the Simple View of Reading so Important?

The Simple View of Reading helps us understand how people read by looking at two main things: recognizing words and understanding language.

By figuring out where someone fits on this reading scale, we understand why reading might be hard for them and what we should help them with.

Examples of Instructional Practices Aligned With the Science of Reading.

Word Recognition Practices

- Phonemic awareness and letter instruction.

- Explicit and systematic instruction in how to decode (read) and encode (spell) words

- Connected text reading to build reading accuracy automaticity, fluency, and comprehension.

Language Comprehension Practices

- Read-alouds from a variety of complex texts to build knowledge and vocabulary.

- Robust conversations to develop students’ academic language

- Explicit instruction in grammatical structures and academic vocabulary within the context of other reading activities.

Examples of Practices NOT aligned with the Science of Reading

Word Recognition Practices (NOT aligned with the SOR)

- Emphasis on larger units of speech (syllables, rhyme, onset-rime) rather than individual phonemes.

- Implicit and incidental instruction in word reading.

- Visual memorization of whole words. For instance, using word shapes.

- Guessing words from context.

- Using picture cues.

- Skipping words.

- Emphasis on speed or words per minute over accuracy when reading texts.

Language Comprehension Practices (NOT aligned with the SOR)

- Read-alouds from leveled texts that students will be reading so that text is not sufficiently complex.

- A lack of explicit instruction of morphology, memorization of isolated words and definitions out of context, and a lack of strategic and intentional instruction.

- Implicit instruction of grammatical structures.

The Science of Reading and Learners with Linguistic Differences

The Science of Reading includes learners with linguistic Differences, such as Multilingual Learners (MLLs) and English learners (ELs),

These students also benefit from the practices derived from the science of reading.

Conclusion about the SOR

There’s way more to the Science of Reading than this, but hopefully you’ve understood that this is NOT a phonics program, but a set of guidelines BASED on science and research done over decades by researches of multiple fields, that ANYONE involved in the process of teaching reading can refer to TO SELECT and implement practices about reading that will be the most effective for the most students.

Resources for Further Exploration

If you want to delve deeper into the Science of Reading, consider these resources:

Website:

Books:

Reading in the Brain, by Stanislas Dehaene.

A leading neuroscientist’s exploration of the reading process and its implications.

Great book if you want to understand exactly what happens in the brain when we learn to read, why is it that we are even able to read, how the brain of an illiterate person is different from a reading brain, what exactly is going on in the dyslexic brain, and much more.

The chapter about dyslexia is my favourite one. So much so that I created a whole article summarizing the main insights, findings and ideas from this chapter!

With robust science, Dehaene also debunks some flawed thinking behind whole-language practices, such as the assumption that we are wired for learning to read.

The book contains a wealth of interesting information, although some of it may be challenging for non-experts in neuroscience. However, there is also plenty of actionable information, such as recognizing red flags that may indicate dyslexia.

If you’re interested in gaining a modern scientific understanding of dyslexia, this book is for you.

Language at the Speed of Sight: How we Read, Why So Many Can’t and What can be Done about it, by Mark Seidenberg.

Fascinating and thought-provoking book. This book confirms the effectiveness of phonics in teaching reading with scientific evidence.

Once more, you’ll learn about brain science, neurology and the history of reading, but also about what’s been proven to work in reading instruction and what hasn’t.

The ultimate goal of this book is to provoke changes in teaching methods for reading.

If you are an educator who acknowledges the issues within the reading achievement gap, you might see this book as a platform from which to advocate for change.

Shifting the Balance, by Jan Burkins and Kari Yates.

6 ways to bring the science of reading into the balanced literacy classroom.

As the title indicates, it offers practical strategies to bring Science of Reading principles into balanced literacy classrooms.

If you’re shifting from a balanced literacy approach to a structured literacy approach and wish to ensure alignment with the principles of the Science of Reading, this will be a good choice for you.

How to Plan Differentiated Reading Instruction, by Sharon Walpole Michael C. Mckenna.

An excellent resource that will probably make you reconsider your configuration of small groups.

Rather than grouping children by their reading level, this book emphasizes the importance of grouping students based on their individual needs.

What specific skills are they lacking? Is phonemic awareness? Is it reading comprehension?

By grouping children this way, you can truly work on their lacks and see effective skill development.

This is also a highly practical book. You’ll find lots of strategies to address specific learning gaps. The book also includes illustrative lessons.

Speech to Print, by Louisa Cook Moats.

While this book can be dense and hard to digest at times, we have still included it in the list because it is a great reference book.

It covers all you need to know about reading and writing.

What is Orthographic mapping? What is the Simple View of Reading? What is the difference between vowel and consonant phonemes? How do we build words? How does the Syntactic System work? How does morphology work and why is it so important to become a good speller?

Uncovering the Logic Of English, by Denise Eide.

Do you believe there’s no logic in the English Spelling system? Do you believe it’s just formed by exceptions on top of exceptions?

If so, this book will probably make you change your mind.

While not as straight forward as most phonics-based languages, the English spelling system has some logic behind it after all.

This book reveals some tools that will help you unlock its intricacies and teach them to your students.

Equipped for Reading Success, by David A. Kilpatrick.

A comprehensive, step-by-step program for developing Phonemic Awareness and Fluent Word Recognition.

This book summarizes what the latest research about how we learn to read, and has a strong focus on the development of phonemic awareness, as the key to help struggling readers.

If you work with struggling readers that lack phonemic awareness, this book will be an excellent resource.

These resources provide insights, strategies, and a scientific perspective on reading instruction.

Conclusion: Balanced Literacy VS Structured Literacy (SOR)

The Balanced Literacy vs. Structured Literacy debate has a long history, but the Science of Reading is changing the landscape of reading education. By understanding the scientific principles behind reading, educators, parents, and tutors can make informed choices to support children in their reading journey.

We hope this blog post has shed light on this critical debate and its implications for teaching reading effectively!

Hey there! I’m Laura – an author, YouTuber, blogger, and the creator of the “Learning Reading Hub” platform. I created this space to dive into the world of reading instruction and to shout from the rooftops about how vital it is to use the right methods for teaching reading. I’ve got a TEYL certification (Teaching English to Young Learners), plus a Journalism degree from the University of Navarra in Spain, along with a Master’s Degree in Communication.

I’ve always loved digging into research, jotting down my thoughts, connecting with people, and sharing what makes me tick. With a background in marketing, digital projects, and the education scene (especially language learning), I’m all about wearing different hats.

When my first kid needed to learn how to read, it opened my eyes to the challenges and complexities involved. This journey took me through a rollercoaster of self-teaching, eye-opening discoveries, and yeah, some letdowns too. There’s so much conflicting info out there, along with methods that just don’t cut it. And let’s face it, these issues are way too common.

Now, I’m all about channeling that passion (without sounding like a know-it-all!) and sharing my journey. My mission? Making it easier for those who are on the same path I once was.

My heart’s with my family and the amazing Learning Reading Hub project. I live with my husband and two little ones, raising them in a bi-lingual environment (English and Spanish).